Rethinking food deserts

|

For the last decade, research on neighborhood health has focused most heavily on the influence of the physical and social environments on health related behaviors. Research on food deserts—low-income, usually urban communities where healthy food is inaccessible or relatively expensive—has received particular attention from media outlets and policy makers. Food deserts have been largely designated through simple methods of spatial analysis, most often based on the distance to the nearest grocery combined with aggregate census data. Work in this area has resulted in policy initiatives at a variety of scales meant to improve food access primarily by incentivizing the creation of new groceries and supermarkets. By improving the supply of healthy foods to low-income neighborhoods through the creation of new food retail sites, these policies aim to improve dietary habits, reduce rates of obesity along with their social and health costs, and contribute to neighborhoods’ economic revitalization. In this way, I argue that these policies represent a spatialized form of Soss, Fording, and Schram have described as neoliberal paternalism, aiming to foster citizens less financially burdensome and politically dangerous to the state through partnership with private industry and conventional systems of food production and distribution.

|

|

|

A handful of recent studies have also begun to question the data, methods, and conceptual underpinnings of much food desert research. I argue that its shortcomings are largely due to a singular focus on the supply of healthy foods in low income neighborhoods. Relatively little attention has been paid to the demand for food in these communities, specifically the factors shaping interactions between individuals and their “food environment.” By largely ignoring individuals’ social networks, cultural preferences, and class identities, the vast majority of current work neglects the range of ways people understand healthy food and desirable food sources. Food procurement is treated in

isolation from other aspects of individuals’ everyday mobility, including

travels to work or time with family. This work also rarely studies informal

sources of food in low-income communities, including food shelves, bartering

with friends and neighbors, and self-provision/gardening. By crafting an alternative approach that accounts for these factors, my research attempts to explicitly account for how the everyday experience of poverty, inadequate transportation networks, and limited food options shape how areas labeled as food deserts are experienced by their residents and suggest alternative routes for strengthening urban food systems

|

|

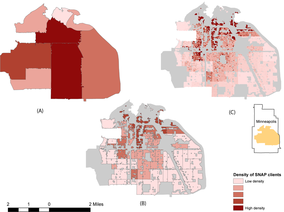

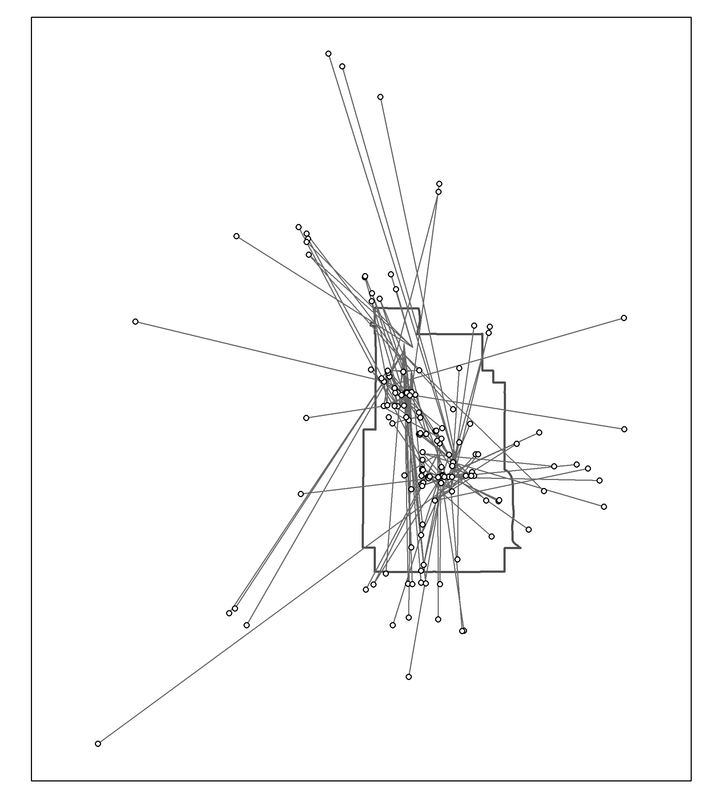

My empirical work has two main components. First, I have transformed data from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) to allow for neighborhood level analysis of benefit redemption patterns, including net inflow or outflow of SNAP dollars, redemptions by store size, and the role of small and ethnic-specific retailers. Despite its obvious relevance to discussions of food access, studies of neighborhood food access have thus far failed to analyze SNAP data.

Second, I selected two Minneapolis neighborhoods based on their high SNAP participation rate and contrasting levels of food access. A cohort of about 30 study participants within each neighborhood (total n≈60), stratified by race and immigration history, are using GPS enabled smartphones to record their daily mobility and reflect on their food procurement for a one week period. By comparing SNAP data with these largely qualitative case studies, this research will provide a more sophisticated understanding of individuals’ interactions with their urban food environments, suggesting new approaches for improving the health and equity of urban food systems. |